Improving Low Compute Language Modeling with In-Domain Embedding Initialisation (Welch, Mihalcea, and Kummerfeld, EMNLP 2020)

This paper explores two questions. First, what is the impact of a few key design decisions for word embeddings in language models? Second, based on the first answer, how can we improve results in the situation where we have 10 million+ words of text, but only 1 GPU for training?

The impact of tying, freezing, and pretraining

It is standard practise to tie the input and output embeddings of language models (i.e., use the same weights in both places), training them together and initialising them randomly. Several papers have shown that this improves results by providing more frequent updates to the input embeddings. But if you have data available for pretraining it is less clear that this is the right approach. To explore this I’m going to use a few symbols:

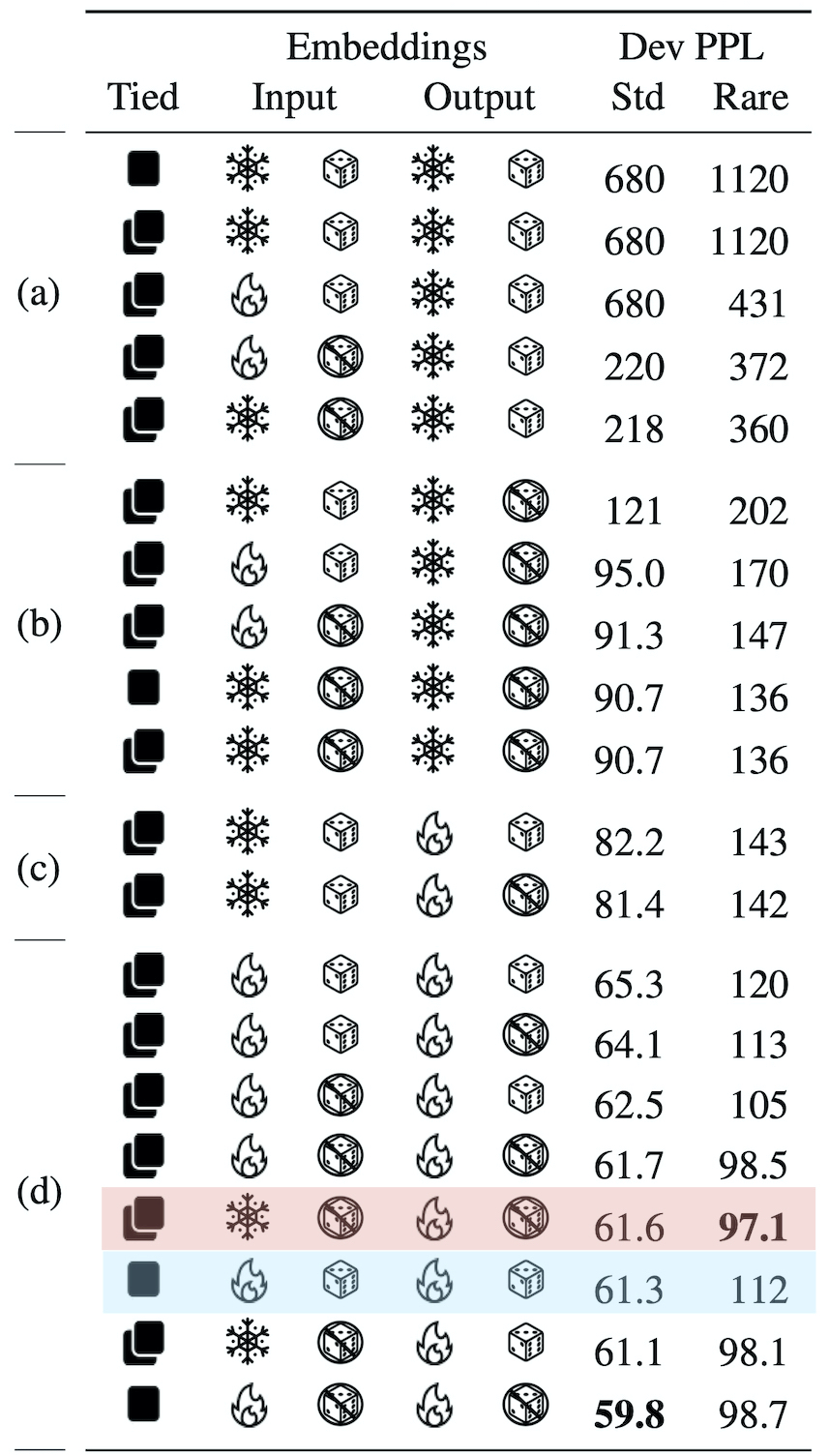

Here are the results of training an AWD-LSTM with all variations of these parameters, evaluated on the standard LM development set of the PTB (Std) and a variation that has actual words instead of unk (Rare):

Light blue shows the standard configuration and light red shows our proposal. The table is ranked by performance on Std and has four clear sections:

(a) Frozen random output embeddings.

(b) Frozen pretrained output embeddings.

(c) Frozen random input embeddings.

(d) Various configurations.

I was surprised by the dramatic difference between input and output embeddings here. Freezing the output embeddings, even with a good embedding space, leads to terrible performance. In contrast, freezing input embeddings is fine if they are pretrained, and has a far smaller impact when they are random.

Evaluating with rare words, the big picture is mostly the same, but pretraining has a bigger impact. One interesting difference is that the top five models all use pretrained input embeddings, with a large gap from there to the next results. At the same time, pretraining the output embeddings seems to have only a small impact (when holding all other variables fixed). Finally, the best results freeze the input embeddings. Our explanation is that embeddings become inconsistent when they aren’t frozen. The vectors for words in the training set are moved but the ones seen only in pretraining stay where they are, leading to an inconsistent embedding space.

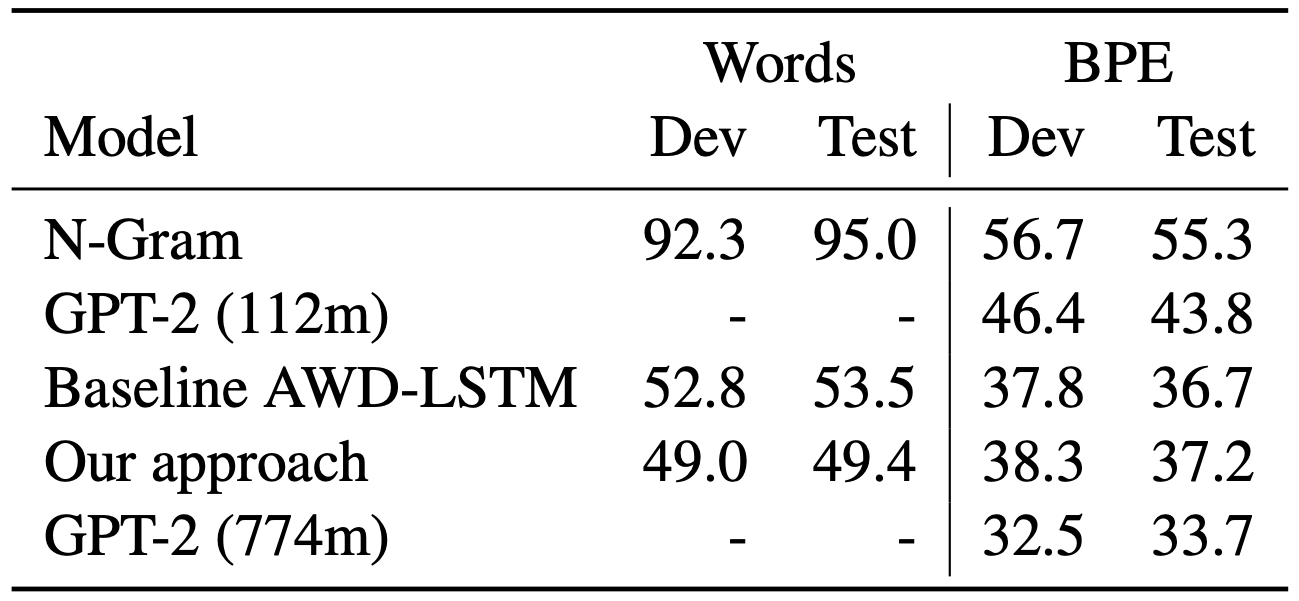

The paper then goes through a series of experiments to explore this, varying data domain, similarity of pretraining data, and more. Here I’m going to jump straight to the final results. The table below considers a dataset with 43 million in-domain tokens for pretraining and 7 million for LM training. The other models are the standard AWD-LSTM, an n-gram language model, and two version of GPT-2 (without finetuning):

For word level prediction perplexity is reduced by 4. However, if we train and test with BPE there is no improvement (see the SHA-RNN paper for some issues with comparing BPE and word evaluation). So if your application works with BPE this finding isn’t useful, but for word-level modeling it probably is.

A few notes about this work:

- A natural next step would be to explore ways to train the language model with more data. Modifying the AWD-LSTM code to support training sets larger than GPU memory could render pretraining unnecessary (though at the cost of much longer training). In some experiments (not in the paper), we found that when the pretraining set and training set were the same, pretraining didn’t improve performance, but it did speed up training.

- Properties of evaluation datasets have shaped the direction of work on language modeling. It’s important to think beyond the hyperparameters that are easy to vary (e.g., hidden vector dimensions) when adapting a model for a new scenario.

- Writing robust research code is hard. We tried getting several other models to run with our variations, but going beyond reproducing results to actually modifying code proved hard. Even for the AWD-LSTM, we failed to reproduce results except when we went back to one of the earliest releases.

- This paper was saved by author response. The initial reviews were 3.5, 2.5, 3.5 and based on the response and reviewer discussion the 2.5 went to a 4. The response contained answers to reviewer questions, including a bunch of statistics about the data that are now in the final paper. I have always been a fan of author response. It can lead to more informed acceptance decisions and more useful feedback to authors. To achieve that, both authors and reviewers need to engage with it though. In particular, reviewers need to give something of substance to be responded to and they need to carefully read and consider the response.

Citation

@InProceedings{emnlp20lm,

title = {Improving Low Compute Language Modeling with In-Domain Embedding Initialisation},

title: = {Improving Low Compute Language Modeling with In-Domain Embedding Initialisation},

author = {Welch, Charles and Mihalcea, Rada and Kummerfeld, Jonathan K.},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing},

month = {November},

year = {2020},

url = {https://www.jkk.name/pub/emnlp20lm.pdf},

abstract = {Many NLP applications, such as biomedical data and technical support, have 10-100 million tokens of in-domain data and limited computational resources for learning from it. How should we train a language model in this scenario? Most language modeling research considers either a small dataset with a closed vocabulary (like the standard 1 million token Penn Treebank), or the whole web with byte-pair encoding. We show that for our target setting in English, initialising and freezing input embeddings using in-domain data can improve language model performance by providing a useful representation of rare words, and this pattern holds across several different domains. In the process, we show that the standard convention of tying input and output embeddings does not improve perplexity when initializing with embeddings trained on in-domain data.},

}

Tables in written form

Table with training variations

Each section is presented separately below, with the model described using five words followed by the result on the standard data and the result on the data with rare words.

First section:

- tied frozen dice frozen dice, 680, 1120

- untied frozen dice frozen dice, 680, 1120

- untied unfrozen dice frozen dice, 680, 431

- untied unfrozen train frozen dice, 220, 372

- untied frozen train frozen dice, 218, 360

Second section:

- untied frozen dice frozen train, 121, 202

- untied unfrozen dice frozen train, 95.0, 170

- untied unfrozen train frozen train, 91.3, 147

- tied frozen train frozen train, 90.7, 136

- untied frozen train frozen train, 90.7, 136

Third section:

- untied frozen dice unfrozen dice, 82.2, 143

- untied frozen dice unfrozen train, 81.4, 142

Fourth section:

- untied unfrozen dice unfrozen dice, 65.3, 120

- untied unfrozen dice unfrozen train, 64.1, 113

- untied unfrozen train unfrozen dice, 62.5, 105

- untied unfrozen train unfrozen train, 61.7, 98.5

- untied frozen train unfrozen train, 61.6, 97.1

- tied unfrozen dice unfrozen dice, 61.3, 112

- untied frozen train unfrozen dice, 61.1, 98.1

- tied unfrozen train unfrozen train, 59.8, 98.7

Final results table

Models with word level evaluation, giving development results then test results:

- N-Gram, 92.3, 95.0

- Baseline AWD-LSTM, 52.8, 53.5

- Our approach, 49.0, 49.4

Models with BPE evaluation:

- N-Gram, 56.7, 55.3

- GPT-2 (112m), 46.4, 43.8

- Baseline AWD-LSTM, 37.8, 36.7

- Our approach, 38.3, 37.2

- GPT-2 (774m), 32.5, 33.7

Acknowledgements

Dice Icon by Andrew Doane from the Noun Project. Fire and Snowflake Icons by Freepik from www.flaticon.com.